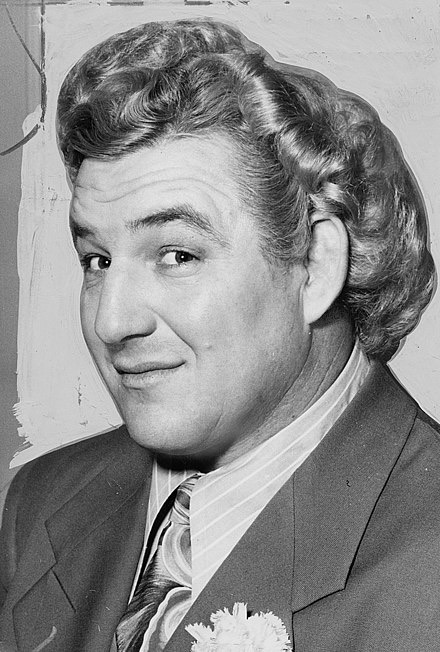

Top: Odetta at Maxine Mimms 80th birthday party, December 8, 2008 (Photo: De Danaan)

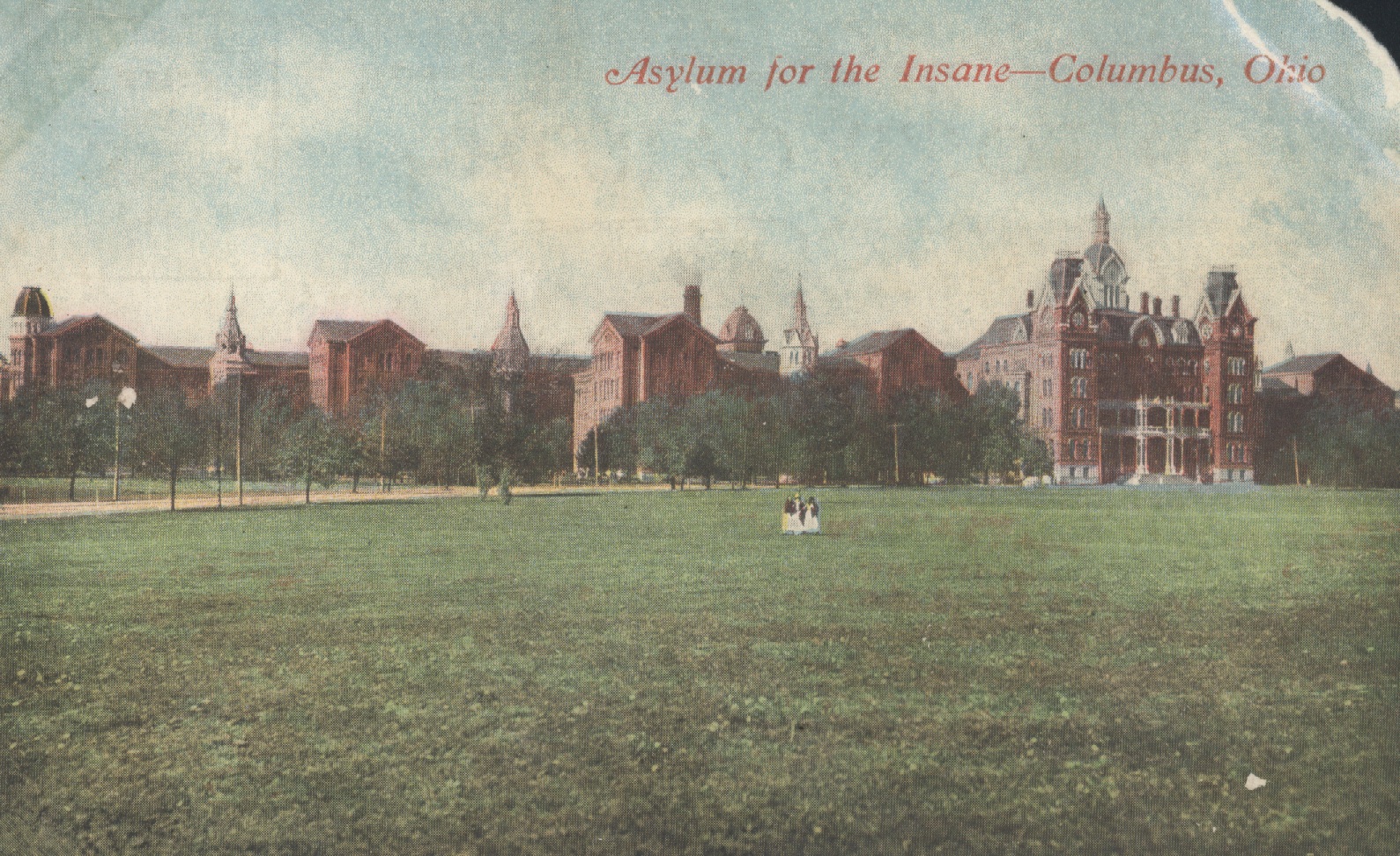

Bottom: Maxine Mimms at home on Oyster Bay, 2010 (Photo: De Danaan)

ODETTA and MAXINE

by LLyn De Danaan

Nearly three decades following the launch of her career in folk song, in 1982 Odetta (born Odetta Holmes, 1930-2008) was teaching a music course as an artist-in-residence at Evergreen State College in Washington. When an interviewer asked about the content of her course, Odetta replied that her students “don’t have a lot of reading or assignments or papers to do. What we’re doing is confronting the biggest dragon in our world, ourselves. We’re battling that feeling our world, our social system has taught us—that if we really display or show ourselves, nobody would like us.” What may at first seem like a saccharine reply in fact constitutes the defining journey of Odetta’s life as a folklorist, artist and activist. Hers is a story of forging an individual identity as an empowered black woman performer at a time when she felt immense pressure to fade into invisibility. Self-consciousness and rage marked the beginning of Odetta’s career, a “beast” inside which she consoled through a full-throated entry into an emerging folk music revival.

Excerpt: Zapruder World: An International Journal for the History of Social Conflict

Maxine Mimms has been a friend of mine since the late 1960s and a neighbor since the mid 1970s. One day, years ago, I asked to talk with her about her friend Odetta. We did a taped interview. There is a lot published about Odetta’s public life, her music, her contribution to social justice movements and activism. I wanted a little glimpse of the private Odetta. Maxine knew her well and traveled with her. She agreed to a conversation.

I: Let’s talk about Odetta. Did you sit around and talk like this? The way we do?

N: Yes.

I: What did you do?

N: Well, the thing that … You know, I was thinking when you called me and said that. What is the informal part of Odetta that I want the world to read about because they know the formal part. But Odetta was a full-grown chronologically mature woman and a total child in the informal thing. Just an innocent … she could pick up. She looooooooooved beauty. You are driving along the highway, and she shrieks “Stop!” You think there is a serious thing occurring, and that you are going to have to turn off to get to the medic … “Look at that gorgeous dandelion coming out of all of those brown leaves.” And you really want to curse her out because you’ve almost endangered your life to stop.

Actually, she had very delicate, delicate movement of her hands. It was … You know when babies lift their hands for you to hold them up, when Odetta picked up a leaf or a flower, it was always almost like a baby, just seeing something for the first time. She was totally, absolutely the most gifted professional artist with the innocence of the environment and truly loved the environment.

So, when she would sing about the environment or the songs about people, she actually became that. When I met Odetta, she had not she did not sing with her eyes open because she … the pain of looking at the audience was too great. Her music was so much inside of her navel, inside of her intestines that she couldn’t open her eyes like most artists and just relate to the audience.

She related to the guitar, and the way she sat in the chair, her feet … I never knew this until I took pilates, but her feet were always flat on the floor. She said Alberta Hunter taught her that. She said Alberta Hunter taught her how to keep her feet flat on the floor and be in tune with nature. Now this sounds so crazy. Here you are in a place made out of wood or cement or something, but your feet are flat on the floor to be in tune with it.

And when I took pilates, I thought she was talking about balance. I didn’t know what she was talking about. She was talking about singing not only with her mouth, but with her spine. That’s when I discovered who Odetta was. One of the reasons she was so great is that she sang with her mouth, her heart and her spine. She incorporated all these levels of her being, which brought you, the person that’s listening into their five senses. Odetta’s music just didn’t reach the ear, she was aesthetically gorgeous. That’s why she came out with the little thing hanging … that’s why she had a natural. She was the first black woman in the country to wear what we call a natural, that is her hair not pressed. Years ago, they used to call it “You’ve got an Odetta.”

I: Oh, really!

N: Long before it was a natural. You’ve got an Odetta. And it’s ah ha ha … because Odetta came forth to us with this dark skin. Remember now, our society had dealt with the Billie Holiday female. That’s coffee-looking, but caramel-looking and had dealt with the mixed-looking Lena Horne So when Odetta came out strumming a guitar and a voice that had three to four octaves that you could hear, which was actually opera. Now we call it folk music, but it really is opera in several different acts, with a prologue and epilogue and all that. That’s who Odetta introduced to us. But, Llyn, she introduced the way to taste … to see the music, taste the music, smell the music, hear the music and feel the music. All five senses were engaged when you listen to her in a formal thing.

But having lived with her, having been around her, night and day in and day out, what you saw on the stage when she went home, she would breathe and exhale and breathe. I would be with Odetta when her concert was over at 11, and I’ve seen it take from 11 to almost 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning for her to what I would call “come out of it” or come down. And her coming down was simply through breathing. It was the most amazing thing I have ever experienced in my life.

Now, I’ve been around a lot of artists, but hers was the most, hers was the longest experience of coming out of it and coming down than any of the other artists I’ve met, and I didn’t realize until I … really maybe until the last time I saw her, which was my 80th. (Referring to her own 80th birthday in 2007) I didn’t realize that because folk … I thought Odetta is a folk singer. I didn’t realize that what … that the opera training that she had … she was a storyteller, which is about the folk, but she made you, through the rhythm of these lyrics, feel the experience. So when she went home (from a performance), she had to leave Ireland to come home to her own house, she had to leave the hills of West Virginia, she had to leave everywhere.

So when she went home to her home in Central Park in New York, she had to actually come home, go upstairs in New York and get on whatever psychological plane or state or whatever she had and come home. It was something to watch. Sometimes, she would cry, and there was … I didn’t know the reason. When I first was around, I said, “What’s the matter?” And she would just do like this … “There’s nothing the matter, Maxine.” (Maxine moves her hands)

I: Just wave her hands at you?

N: Yeah, she would just wave her hands. “Shut up.” Because there was nothing as painful as but she just left Ireland. She just left … She just finished peeling potatoes. Or she just finished with the hammer. She just finished getting on the ship of Amazing Grace. She just finished bringing the slaves. She just finished delivering a shipload of slaves. And got them off. Every formal presentation was experienced when she got back to the hotel room by decompressing. Ah, I never thought of that … that word, by “decompressing.”

Before her concerts, she would always drink black coffee with lemon in it. It is the nastiest tasting stuff I have ever experienced in my life. They had to have that in the room. I mean Ohhh. And then, I decided once she died, I wanted to taste it. It is … now to her it was something like a contrast in terms of the sourness of the lemon, and I guess the strongness of the coffee. I don’t know but I imagine she needed that just like a …

I: Caffeine.

N: It had to have, but the lemons?

I: For her throat, maybe? It’s an interesting combination. I know a lot of people have tea or just honey and lemon in warm water before singing.

N: She had black coffee and lemon, and Llyn, at 80 years old, her voice… and Maya Angelou and I talked about it…. her voice was still as strong as it was at 19. At her memorial, Harry Belafonte talked about that voice that he discovered way back when he discovered Odetta … He talked about it. A lot of people have talked, since she’s died, since her death about how that girl kept that same voice. But I watched her breathing. Her breathing … her exhaling and inhaling was like something I had never experienced before in my life. She took long … oh, now I just thought of this … I really believe when Odetta got back to the hotel room. I really believe that what I experienced was a long-term experience of some degree of meditation that I didn’t know anything about. Because her breathing was just profound. She could actually breathe.

What killed her, I believe, was her inability to breath … this is stupid … when she got to the hospital because a lot of people talk about that’s all she tried to do. She said, “If I could just get a good strong breath.” She really believed in whatever the breathing was. Experiences. And somebody had … Her feet flat on the floor. She believed in that. That’s why she sat on the edge. She always sat with a stool, a round stool, and she sat on the edge of that stool with feet on the floor when she sang. It’s almost like a sitting/standing position. I don’t know whether you can …

I: I do understand what you’re saying.

N: Well, she kept her spine … Her singing was from her heart, her mouth and her spine. I have heard her even say that. I’ve got to keep my spine straight. She walked like a horse, you know. She walked like a horse. She took long steps, long … walking with her in New York was a very painful thing for me because I’m looking in the stores and everything, and she’s saying, “Come on.” And I’m, you know, I took five steps to her one. She walked like a thoroughbred, I mean, a horse.

I: She was tall.

N: Yeah, but she stretched her legs.

I: She stretched out when she walked.

N: She stretched out when she walked. And she could stretch out notes too. I didn’t know that very much about the spine, but I have heard her talk, you know. Her sitting was always exaggerated to me. But she made a big deal out of sitting tall and singing tall. She talked about singing tall and singing straight and singing from the heart, singing from the spine, and singing … I don’t think I have ever heard Odetta talk about singing from the diaphragm. I thought maybe she learned something about the spine, and I thought we did not have a diaphragm because everyone I knew talked about singing from the diaphragm and breathing … she talked about her spine. I don’t know where that came from other than she believed … I believe that the sound came from back here and in through here or something, and she always kept herself expansive. I don’t know that much … I never could get that much.

It took her a long time to cook because she … I remember one time, she said she was going to fix me a dinner. I’ll never do that again. I have never done it since then. She went to the store. She loved going to the store, but she bought stuff that she really didn’t use. She just … because it was pretty. “Look at that beautifu,l beautiful squash.” And beside the squash would be a big gorgeous purple something, and she’d say. “Oh, I want to get that. Isn’t that beautiful?” And she’d put the two things together, the yellow squash and the purple something and then a cabbage and that, and she saw the beauty of that. She didn’t use it. She just bought it. She told me. She said, “I want to fix you … “ Oh God, Llyn, she said, “I want to fix you … Oh, I am going to get a Cornish game hen, and I’m going to …”

Well, a Cornish game hen is small, and she seasoned that thing in the kitchen with a little piece of garlic this and a little piece of purple that and green this. I think she told me at 10 that morning. She wanted to make sure that I had something beautiful. It was 8, 9 ‘o clock in the evening before she put that Cornish game hen in the stove. After she had petted it and decorated it and talked about its wonderful skin and apologized to it for having been killed for us to gobble up.

When she finished, I could have ordered a pizza and been through with it and everything. And to have meal with her was like going to a … to have a meal with her was like touring a foreign country. She went down each item on the menu and talked about its coloration. You know, what structure the spinach salad had, how the eggs were scraped or where the eggs were sliced. Whether the eggs were whipped with a fork or whipped with a beater. Never, ever allow your eggs to be whipped just with a beater. Always use a fork. Don’t ask me why, but we would go through this. So ordering breakfast was an experience.

Everything with Odetta was an experience, not just a something. You know what I am saying. You go to breakfast. You’re going to be there until lunch, not with eating, but just with talking about the menu, each category. When the food got there, she would spend time talking about where the rice came from, the brown rice out of this part of China. All levels of China didn’t have the same kind of brown rice. Odetta was folk music, if I can put it like that. Odetta was opera. Odetta was not the singer of these. She was it. Believe you me, Llyn, she was it. She could tire you out because her brilliance in terms of her craft, if I can use that word, was so intimate and profound. I will use Amazing Grace. One time we were in Canada, in a very small town up in Nova Scotia? Am I right? (Ed. Note: Maxine said Newfoundland here, but later corrected it.)

I: Um hum.

N: Way up, and there was a church, historic church, a little town where people didn’t drive for the concert. They kind of walked, and it was extremely wonderful. I was … my limited knowledge, I just felt like I was in the chalet. Okay? Odetta went in, and she just … everybody in there was white, except the two of us, and she came out, Llyn, and all of these white white white people … I’m sure they were the 1960s type because the women had allowed their hair to grow. Nobody manicured like grass. Nobody. Everybody looked … and the hospitality was extreme.

You know what I mean. It was a welcoming, which put Odetta into her world that she likes to go into. So she became a part of that 1960s type reunion, you know. And she just sang, and I’ll never forget, Amazing Grace. She slowed it down. Everybody in the audience … and she said, “Sing with me.” They sang with her, and she wanted to do, in her head, I could just cry thinking about this. What she did, Llyn. Here’s an audience women, men, all remembering something of whatever they were remembering, Amazing Grace. They harmonized. This is just … with nothing but the guitar and this crowd of people, with this gorgeous looking queen type woman, sitting on this stool.

And Llyn, at the end, she … the room just went silent. Nobody was directing. The room went silent, and Odetta just … um … hit that final note like a benediction. We must have stayed in there after the close of the concert for umpteen hours. It was the most releasing experience that I have ever experienced in my life, and I looked up, and she couldn’t move. Nobody in the audience could move. I didn’t move because I didn’t know whether to throw up or cry. I didn’t know what to do because you don’t. The emotions are so great.

Her intimate concerts were the greatest you could see. The large auditorium concerts obviously were not as intimate. She did things with her voice when the crowd was two hundred to five hundred very different than she did with three thousand and ten thousand. On the three thousand and ten thousand type audience, she was on the stage, and she carried it, but you could hear her having to carry it. The two hundred to five hundred, she sang to each individual.

I: Hmm.

N: Now that’s stupid, isn’t it?

I: No. Nothing is stupid. (Short silence) Do you need a glass of water?

N: No, I’m just trying to think of how to give you that language. The smaller the crowd, the more intimate the story. And she did things. I’ve heard her … I heard 26 million versions of Amazing Grace.

I: Yeah. Depending upon …

N: The audience. The size. The size. Her music was about intimacy. Her delivery was about, “How intimate can I get with you with the story? Can I get you to see the people with the potatoes? By the way, can I get you to help me peel this potato?” Llyn, that’s how close it was. And you could feel the potato farmers. You could feel the miners in West Virginia. You actually went in the mine with them, and you got so pissed because you didn’t want another mine explosion when she finished. And when she did On Top of Old Smoky, “all covered with snow,” you actually could see the scene the sex scene, the way she handled it. Home on the Range, I’ve heard her do many versions of that. When she did Home on the Range, “where the buffalo roam” and when she would get to “buffalo,” something she would do with the guitar to let you know, with global warming, the buffalo is disappearing, and she’d “Ha ha ha ha.” And when you finished, you’d gotten, you’d want to sign up to do something with the people that didn’t understand climate change or she made you understand the ignorance in the society when they didn’t understand Home on the Range.

Rock-a-Bye Baby on the Treetop. I’ve heard one thousand versions of that. “When the wind blows, the cradle will rock. When the bough breaks”… and she would look around, “the cradle will fall. Down will come baby, cradle and all.” The collapse of all of our images that we have held artificially, and now that I’ve been talking to you, including the concept of retirement, what Rock-a-by Baby on the Treetop, she would take our nursery rhymes and make us see what we had bought into, and how lots of them would cause us to be unkind to each other and be judgmental, and the disappearance of these things through a vocabulary of inexperience.

Folk music to her was a way of life. I mean it wasn’t the stage, and she went home, and she wasn’t on the stage. She stayed permanently on the stage, 24 hours a day. She was always with the vocabulary. Is that right? Yes. She was always with the language of her craft. Day in and day out. And it was only through breathing that she would pull herself away from a previous … Isn’t that interesting?

I: Let’s take a pause. Take a little pause.

N: Isn’t that interesting. Just talking about her. She was a wonderful person.

I: I know. Let’s just take a little pause. Let me make sure. I am taking a lot of notes because I do not trust …

N: Well, talk to me because, is my vocabulary okay because I’m trying to describe her?

I: Your vocabulary is splendid. No, it’s everything you’re saying is absolutely splendid. It’s wonderful.

N: It’s hard to talk about her because she was something. Just being with her …

I: Now we are recording again. Yes.

N: Do you want to turn it off or do you want to do now?

I: Oh, no I want to keep going if you’re okay with keeping going? Did you want to take a drink or anything?

N: Yeah, why don’t we … No, we can keep going. You want to ask me something?

I: Well, yeah. Now I’d like to because it was kind of right where you left off. I mean you talked about living with her, being there in the hotel when she comes back from a performance, traveling with her. Maybe you could start a little bit in the beginning. How you got to know her, where you first met each other? You know, what period? What time periods we are talking about?

N: I met her long before she came to Evergreen, but I didn’t know her. I met her at … where was it? Somewhere in San Francisco at some sort of coffee house. I just went to see her. She and Nina Simone were doing something. I went down with Marie Fielder, and I went down to some little coffee houses. Marie lived in Berkeley.

I: That’s right. I remember where Marie lived.

N: Marie lived in Berkeley, and she said, “You’ve got to come over and see Nina Simone.” Well, Odetta was the lead for Nina, and we were back to the Berkley-San Francisco time. That period was a period when you were just getting ready to … Maybe I’m … I hope I am right about this … when you had … coffee houses were just becoming popular, the introduction of different kinds …

I: Are we in the 1960s or ’70s?

N: 60’s.

I: We’re talking about the 1960s. Sometime in the 1960s. Coffee house. Well, that’s the period when the first Berkeley Folk Festivals are late ‘50s and early ’60s.

N: Well, Marie … I went down … Marie and I were consulting a great deal at that time, and Marie would come up here, and I would go down there. And we went over, and we were introduced to her. And she was gracious but distant. And that’s fine. Marie was a real gorgeous … Marie looked just like Lena Horne, and a very outgoing type person. I just … I wasn’t paying that much attention to anything but education at that time. (Ed. Note: that was 1967 according to later comments.)

And then, Evergreen wanted her. Evergreen State College in Olympia wanted her. And I can’t remember the year, but Betsy (Elizabeth Diffendal, faculty at Evergreen) said … Betsy loved her music from the ’60s.

I: I know that.

N: She said, “Would you pick her up at the airport?” I said, “I’d be glad to.” And the rest is history. (Ed. Note: that was 1982)

I: So this was before The Color Purple because I remember you went to some hotel with Odetta and a whole bunch of women to give support … to Walker. That was after …

N: Odetta, Toni Morrison … The movie came out (Ed. Note: 1985), and there was a lot of …

I: Yeah. Backlash.

N: Backlash. And we were invited to support Alice Walker. And that’s how I met all of them.

I. So she came to Evergreen…

N: Yes, and Maya (Angelou) was in town.

I: Maya was in town.

N: And we brought Odetta to Olympia. Maya was staying in a Tacoma hotel. I think it was the Sheraton, at that time.

I: So you all knew each other at that point?

N: Yeah. And we brought Odetta down here. And then …

I: Here, meaning to Olympia or to your house?

N: No. Odetta came to a hotel in Olympia. And Maya was speaking on the Tacoma campus. I picked Odetta up to come from here to hear Maya at the Tacoma campus. (long pause) And we went to Betsy’s house afterwards, and then Maya stayed for a couple more days in Tacoma, while Odetta negotiated her contract and space here. Evergreen had already gotten a house for her. I think when I think about it, I believe it was … I know Byron Youtz had a lot to do with negotiating the money, the house, the rental car and everything. He wanted to hear her badly, Odetta. Byron.

I: How long? Was she here the whole time? I wasn’t here that year, so she was …

N: A year.

I: She was here for a year? And that’s when Evergreen had “visiting artist” contracts that they put out, and I don’t know if anybody else was here on a visit that year. (Ed. Note: see below. There were two Artists in Residence at Evergreen in 1981-82, perhaps with very different contractual arrangements.)

N: She was the last one. She was the first and the last.

I: She was the first and the last?

N: She taught, and she gave a concert. A big concert in Washington Center. And while she was here, she was allowed to do her performances. That was one of the best contracts (the contract made with her by Evergreen) that anyone has ever done. We brought her in as an academic, and that’s when other faculty discovered that they could do their work and perform. And Odetta would do … would go away on Friday, do a concert Saturday, and be back for her class on Monday. The other people, by the way, that imitated that model in terms of artists in the United States was Sweet Honey in the Rock. All those women were academicians, and Odetta taught them how to do that by the way. Perform on Friday, perform on Saturday, catch a red eye special and be back on your job, wherever you had to be on Monday. That’s how women in the modern day could do their career jobs as well as remain performers. So now you see built into many many, many art departments, a performance piece as well as the academic

I have known her since about 1967.

I: That’s what I thought. So about ’67 would have been the coffee shop thing, and you had some kind of … Did you see her occasionally during that period?

N: … I would go to New York alone, and I would see Odetta at maybe a thing, but I never became close to her until the Evergreen piece.

I: Not close until after Evergreen.

N: I never … I always had a formal piece, and she always considered me her West Coast friend, but we never became the person that you travel with … I began to travel with her after Evergreen. I took some time off. I traveled with her, and I stayed …

I: So where did you go?

N: Canada …

I: That was … now you said “Newfoundland,” and I said, “Yes, but was it Nova Scotia?”

N: Nova Scotia.

I: It was Nova Scotia, wasn’t it, not Newfoundland?

N: Yeah. Nova Scotia. I went everywhere with her, California, all over Washington, wherever she performed, she would get a ticket for me, and I’d meet her. And then I would stay with her in her apartment in New York, and let’s see, I’m trying to think …

I: And she was … Tell me a little bit about her apartment. So she had a …

N: She lived across from Central Park on … I can’t even think of the avenue now.

I That doesn’t matter.

N: Anyway, 5th Avenue, I believe it was. All the way down to Central Park. And she was one of the few that bought an apartment in that place from a coop point of view. Whatever that meant in the New York area. I think Cicily Tyson and Miles Davis also bought because they didn’t live very from her … down the street from what I understand. She lived across from a park, and you could wake up in the morning and hear the children playing on the swings. And she stayed there until she died.

I: So, she had that when you first met her.

N: Yes.

I: She had that for a long time.

N: Forever. She was totally (pause) an activist. She was born that way, I believe. She came out of Alabama, but her life was New York. I mean her life was California and then New York. She loved New York. She was a private public person.

I: What do you mean by that?

N: Well, after the concerts, she would lock herself up and be in her house until three o’clock in the afternoon.

I: So she … It took her all that time to decompress, and then she slept until

N: She slept or sat and looked out the window. And her equipment check was always at four o’clock wherever she went. She would go to wherever the space was. She would be strong enough at three to get herself ready to go check at four, if she was going to perform that night. And in New York, she performed a lot at St. John’s.

I: How did she … Did she ever talk to you about how she met Alberta Hunter?

N: No, she didn’t, but back in the day, she …

I: That was an interesting thing because it sounds like she did some mentoring for …

N: Alberta Hunter did a lot of mentoring of a lot of the artists in that period, and she was … Oh, when we went to see … when Alberta came back on the scene in New York, Odetta and I went a number of times, and she would … Alberta would invite her up to sing with her, and they would do a duet or something. But Alberta was standing herself. She kept her feet flat on the floor from what I understand from Odetta, and so a lot of the artists imitated her in terms of being able to sing from their spines.

I: Yeah, her story is incredible, isn’t it?

N: Alberta’s. I’ve never known her story.

I: Well, she worked as a nurse for years. You know that story.

N: Go ahead.

I: Well, she … How was that? She sang. I should get that … I’ve got a book about her. My recollection is that she, of course, sang in the ’20s, and she was really well known, and she did all kinds of performance. Then at some point, she stopped and became, I think, a nurse and lied about her age so that she could get qualified or go back to school. I’ll work it out for you. So that’s when you talk about … when she came back on the scene. It was kind of like she was discovered doing this other work, and somebody said, “Alberta Hunter, why aren’t you singing?” So …

N: And brought her back.

I: Yeah, but for years, she was not in the musical world. She was doing …

N: Well, we went to see her, and she was a charming, charming person.

I: Oh, I love her. I had a bunch of her records.

N: Well, she influenced Odetta a lot.

I: I bet. Well she was incredible. She was … I mean she is just … I love her voice, and I love her music, and her voice changed considerably from the ’20s and ’30s. It was mainly richer and more robust in many ways.

N: Odetta’s voice stayed quite robust.

I: Yes, I agree.

N: I was shocked when she came here for my 80th that it was still as robust. I just couldn’t believe she could still do that level of Amazing Grace.

I: Now she came out of Alabama. Do you know about her? No you don’t know anything prior …

N: No. I know her sister very well. I will show you what her sister knitted for me, Jerilee. Her sister came to live with her. Just two of them. I never met the mother. I talked with the mother quite a bit on the phone.

I: When did she come to live with her?

N: The first part of the ’80s. Somewhere in the ’80s, and she died there. Jerilee, Odetta’s sister. About the ’80s, the ’70s or ’80s.

I: Oh, so she was living there in the Central Park apartment.

N: With Odetta.

I: With Odetta?

N: Uh huh, and she died there. It was just the two of them. And then when we went on that cruise, Odetta and I were roommates. Maya’s 75th. There’s a picture in there if you want to take a look at a copy of that.

I: Where?

N: On my piano.

I: Oh, good. Roommates on … that was Maya’s 75th.

N: Uh huh.

I: I remember because you had a little sign up on your door with your names on it. So, she … so you were traveling around, probably mostly through the ’80s and ’90s going to …

N: Well actually the ’80s. Heavy, heavy, heavy in the ’80s.

I: So, did she … you were traveling … sometimes in cars, or you were in the apartment or what have you? Did she like hum and sing to herself or as she’s walking around or was she looking at vegetables and cooking a chicken … Was she always kind of humming or singing, or was that …?

N: She had a spiritual outlet of a scream. It was the excitement of a child.

Oh ooo ah (slightly loud), like that. It could be in a store. It could be anywhere.

I: Oh, interesting.

N: Uh huh. She just … the excitement of discovery with Odetta was just something to behold, and it just so happened that with me being in education, it was never … it was always thrilling to see because I recognized what it was. It could have been disturbing to many other people.

I: (Laughter) Kind of like when you said that she’d say, “Stop the car.” She’s very …

N: I knew it was her discovery experience. She needed that outlet.

I: But she didn’t go around the house going (hums a few bars)? Not so much?

N: She may not have gone around the house doing it, but you could hear her in the middle of the night break into one of the songs that she hadn’t completed at her concert.

I: Ohhh!

N: And when you first heard it, you knew that there was … you thought … you didn’t know what it was. But if she hadn’t completed … or if she had … Okay, she never was concerned about her voice, but she was a fanatic about her equipment. She carried … I am exaggerating. She carried a suitcase of extra strings.

I: I understand that. Okay. Good. This is good. Extra strings. Did she use a pick, do you remember?

N: She used a pick.

I: Did she have like favorites or do you know anything about that?

N: She used a pick, and she used her favorites. It depended … Now that I am thinking about it, I really believe that I saw the larger the audience, the more the pick, the smaller the audience, the more use of the fingers.

I: Ah. That makes very good sense.

N: Now, I’ve been … now that’s me. I’m not … but I observed her so much, and the larger the audience, the more she could remove herself from the participation, and she picked. She stayed much more structured with the larger audience than she did with the intimate audience. The flexibility, the curtain calls, the response to the curtain calls. In the smaller audience, the response was many, many times for brand new songs. The larger audience many times, it was just a repeat or extension of the last song.

I: Okay. That’s interesting. Well, what about, so … Do you remember anything about her guitar, or anything she ever said about it, or how she treated it or whether it … ?

N: It was her baby. It was her child. She treated it like a … I mean, she cleaned it, and she was very protective of the way it traveled. She asked for special protection on airplanes…She always did a blessing over it. She always did a blessing over it. Let’s see if I remember her not ever …

I: Yeah. Think about, if you can picture where that guitar was like when you were traveling or in Nova Scotia in a car. Where was that guitar? Was it in a hard case?

N: A hard case.

I: Must have been in a hard case.

N: Hard traveling case.

I: Hard traveling case.

N: And I remember her babying it but not over babying it. It went in the back. It went in the trunk. It went on the back seat. But it was stood up. It was laid down in the trunk or stood up on the back seat on the floor. She did not allow other people to handle it… she did not allow other people to handle it. She handled it all the way up to … She handled everything with her guitar. And she always said, she can take anything but a technical malfunction. She couldn’t tolerate a technical malfunction.

I: Oh, yeah.

N: Strings broken or equipment going out. She would go crazy. Her own voice … I think she must have just … I think she trusted her voice tremendously because I never heard her saying, “Oh my God, I feel a cold coming on, and therefore I can’t.”

I: She could do anything with her voice.

N: I think she was just a fanatic when it came to technical … that’s what I am saying. She had 50,000 strings stored in her purse, her suitcase, overhead suitcase. I imagine in her bra, but she had her strings.

I: Yeah. Always ready with the strings. Yeah.

N: Oh gosh, yes. And I remember the microphone … Let’s see … she was sitting on the … she sits on the stool, and the microphone had to come right up to where the guitar was, and she very seldom readjusted the equipment. She would have an equipment check at four, and she never …

I: She didn’t need to do anything …

N: She didn’t do anything to the technical setup, but if it wasn’t right, she would not come out. They would have to get it right.

She never touched anything but her guitar. Once she got ready, once she got out of the car and got to her dressing room and went into her meditative state, which you couldn’t talk to her or nothing, and she knew where I was going to be seated, she went into another world, and she stayed in that world. I mean she stayed in … now her … she … Odetta is nothing like Maya. Maya can just talk to you … She could talk to you right up to the time and right after, but Odetta wouldn’t. She went into … she tranced out, and once I got to know her, I then knew why people said she was a distant person. She wasn’t distant, she just … It took her a long time to decompress, and when I found out she became what she was singing.

I: Yes, very clear.

N: I … You’re telling me.

I: What did … so she was living alone for a long time. Her sister died?

N: I don’t know when Jerilee died. I can’t remember. She’s always lived alone.

I: So, she was either alone or with her sister, or when you were visiting?

N: Yeah. That’s how she lived.

I: What did she have in this apartment? Can you remember?

N: It was a museum.

I: Her apartment was a museum? So …

N: Very delicate. Very spiritual museum. You don’t touch a pot, a plant, a bowl, a spoon. You just were there with the stories and history. She was deeply distant and deeply loved through that distance.

I So. Pictures on the wall? Paintings?

N: Paintings on the wall.

I: Can you remember any specific items that …

N: Baskets.

I: Baskets? Native American baskets.

N: Native American, African, Turkish, wherever she went or wherever she … People just sent stuff.

I: So, these are things that either people have given her, or when she was traveling, she would … and then she would just have them around. You are surrounded by really …

… A museum, and she knew where everything was. Everything [last word said in an emphatic whisper] Ev erything.

I: Did you ever hear her talk about her favorite singers or artists or …

N: Harry Belafonte. Abbey Lincoln. Abbey Lincoln and Harry Belafonte and … Nina Simone….… and Paul Robeson.

………

N: Those were her favorites.

Notes:

Linda Thornburg, filmmaker, was teaching at Evergreen State College while Odetta was a visiting artist. Odetta asked her to record one of her regional concerts. You can view Thornburg’s Odetta film at https://vimeo.com/139046240. The piece is called, 2 Odetta: Encore at Evergreen, 1982.

Note: Dale Soules, award-winning actor of stage and television, known for, among other recent works, Orange is the New Black, and filmmaker Bruce Baillie, launched an Artist-in-Residence Program at Evergreen during the 1981-82 academic year.